Crypto-Waqf: Building a Sustainable Islamic Blockchain

The Battle of Sallasil (معركة ذات السلاسل - Dhat al-Salasil) or the Battle of Chains was the first battle fought between the Rashidun Caliphate and the Sassanid Empire. The belligerents met in present-day Kuwait, at the Kazima desert (about 50 km away from downtown Kuwait City) soon after the Ridda Wars were over and Arabia was united under the authority of the Khalifa Abu Bakr Al Sideeq. The battle is named after a stratagem used by the Sassanid Governor Hormozd, who organized and trained his army for a typical war of attrition: a set-piece battle full of head-on confrontation; tying his infantry together with chains. This tactic would empower the Sassanids to stand like a rock in the face of an enemy assault. But these heavy chains had one (in hindsight very obvious) major drawback: in case of defeat the men were incapable of strategic withdrawal, the chains would be transformed to fetters, meaning that Hormozd’s expected strength was his actual weakness (and downfall).

Even though, the Sassanid army was one of the most powerful and best-equipped armies of the time, this major “weakness” in its lack of mobility: was quickly recognized by legendary Muslim General Khalid Ibn Waleed, who mustered his troops (which were fewer in number) to maximize mobility; mounting them on camels and horses as part of a concerted cavalry attack. Ibn Waleed’s strategy was to use his army’s own speed to exploit the stagnant Sassanids. He simply forced Hormozd and his men to carry out marches and counter-marches until they were worn out. Ibn Waleed then struck fatal blows whenever the Sassanids were exhausted. Caught up in their chains, the Sassanid’s were easily routed, and Islam was able to spread north of the Arabian peninsula with Ibn Waleed continuing on to conquer Iraq and Syria within four and nine months respectively.

Now, its time for a new Islamic chain application. A shariah compliant concatenation.

There is no doubt that the blockchain is the building block of the future knowledge economy. Whether its building blockchain airports or even solving environmental issues, the potential of the blockchain is full of promise.

To begin to understand just how blockchain could transform our world, it’s helpful to identify its defining characteristics. Most notably, these include its distributed and immutable ledger and advanced cryptography, which bring a powerful new property to large-scale computer networks: Trust. This ranges from trust in owning a digital cryptocurrency or good, to trust in its origin, or in the veracity of a transaction. Similar, perhaps, to that false trust the Sassanid soldiers put in those rusty battle chains.

Perhaps more important is our trust in blockchain’s decentralized business model, which to me, is similar to the trust exhibited by Ibn Waleed’s army in Allah and their general’s blitzkrieg strategy which essentially decentralized his army. The blockchain’s decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) nature is neutral by definition and highlighted by the fact that all data and code that underpins the blockchain technology is open for all to see.

قال الله عز وجل : ( سَنُرِيهِمْ آيَاتِنَا فِي الْآفَاقِ وَفِي أَنْفُسِهِمْ حَتَّى يَتَبَيَّنَ لَهُمْ أَنَّهُ الْحَقُّ ) سورة فصلت/ 53

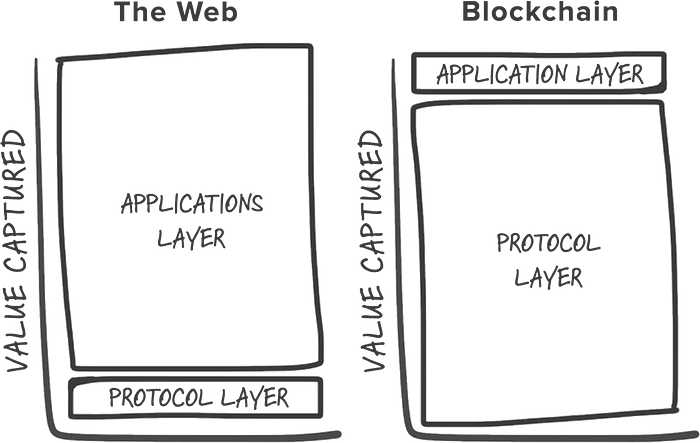

However, despite the hype, considerable challenges must be overcome if the blockchain is to reach the scale and adoption of its general technological forebearers such as radio, television or the internet or more specifically the previous generation of shared protocols (TCP/IP, HTTP, SMTP, etc.). Traditionally these thin protocols produced immeasurable amounts of value, but most of it got captured and re-aggregated on top at the applications layer, largely in the form of data (think Google, Facebook and so on). The Internet stack, in terms of how value is distributed, is composed of “thin” protocols and “fat” applications. As the technology developed, investors have learned that investing in applications produced high returns whereas investing directly in protocol technologies that generally produced lower returns. This relationship between protocols and applications is reversed in the blockchain application stack. Value is concentrated at the shared protocol layer and only a fraction of that value is distributed along at the applications layer. It’s a stack with “fat” protocols and “thin” applications.

Whether primarily thin or fat, these technologies all face the common hurdles of tackling user trust and adoption, performance barriers (including inter-operability, scalability and energy+consumption), security risks (including cyber and identify verification), and legal and regulatory challenges. Once these challenges are overcome, only then will the technology mature allowing its application across different sectors and systems to grow.

Bringing the Blockchain into Islamic Fintech

A waqf (وقف), also known as habous or mortmain property, is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law, which typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for charitable purposes with no intention of reclaiming the assets. These donated assets may be held by a charitable trust. The person making such dedication is known as waqif, or donor, and the waqf is usually considered his or her (family) legacy and as a perpetual source of hasanat (good deeds) until the end of days.

The term waqf literally means “confinement and prohibition” or causing a thing to stop or stand still. The legal meaning of waqf according to Imam Abu Hanifa, is the detention of a specific thing in the ownership of waqf and the devoting of its profit or products “in charity of the poor or other good deeds”.

Another notable scholar, Bahaeddin Yediyıldız, defines the waqf as a system (get ready for the blockchain comparison soon) which comprises three elements: khayrat, a’akarat and waqf. Khayrat (خيرات), the plural form of khayr, means “goodnesses” and refers to the motivational factor behind a waqf organization; a’akarat (عقارات) refers to corpus and literally means ”real estate” implying revenue-generating sources, such as capital markets, land, water wells; and finally waqf, in its narrow sense, is the institution(s) providing services as committed in the endowment deed such as hospitals, schools, mosques, libraries, etc.

The beauty of combining the technological concept of the blockchain with the historical and traditional concept of the waqf is that at their very core, both of these innovations deal in maintaining a sense of public trust for the benefit of society as a whole both presently and towards perpetuity. More on the principle of fidelity to come later.

The Building Blocks of a Waqf

1) Founder

In its simplest form, a waqf is a contract, therefore the founder (also called al-wāqif or al-muḥabbis) must first be of the capacity to enter into a contract. Ergo propter hoc, the founder must:

- be an adult

- be sound of mind and health

- be financially capable

Although the waqf is an Islamic institution, being a Muslim is not required to establish a waqf, and dhimmis may establish a waqf. Note that if a person is fatally ill, the waqf is subject to the same restrictions as a will in Islam.

This is a potential point of conflict that needs to be remedied if we are to develop a true blockchain waqf. Native tokens of state of the art public and permissionless blockchains like Bitcoin or Ethereum, are part of an incentive scheme to encourage a disparate group of people who do not know or trust each other organize themselves around the purpose of a specific blockchain. The native token of the Bitcoin network also referred to as Bitcoin, has token governance rulesets based on crypto economic incentive mechanisms that determine under which circumstances Bitcoin transactions are validated and new blocks are created, but each bitcoin holder’s (or their wallets) are kept completely confidential.

These blockchain based cryptographic tokens encourage “distributed Internet tribes” to emerge — tribes enveloped within a shroud of mystery almost as enigmatic as the identity of the legendary Satoshi Nakamoto. As opposed to traditional companies that are structured in a top manner with many layers of management (bureaucratic coordination), the blockchain disrupts classic top-down governance structures with its secret decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs). DAOs bound people together not by a legal entity and formal contracts, but instead by cryptographic tokens (incentives) and fully transparent rules that are written into the software. We have no idea if these nodes of users are adults, sound of mind and health or financially capable.

2) Declaration of Founding

The declaration of founding is usually a written document, accompanied by a verbal declaration, though neither is required by most scholars. Whatever the declaration, most scholars (those of the Hanafi, Shafi’i, some of the Hanbali and the Imami Shi’a schools) hold that it is not binding and irrevocable until actually delivered to the beneficiaries or put in their use. Once in their use, however, the waqf becomes an institution in its own right.

This one is a bit easier for the blockchain, as a central tenet of the promise of the blockchain is its ability to develop smart contracts between two different users (essentialy a declaration) without the needs to pay hefty middleman fees. This is nothing new, since as early as n 1994, Nick Szabo, a legal scholar, and cryptographer, realized that the decentralized ledger could be used for smart contracts, otherwise called self-executing contracts, blockchain contracts, or digital contracts. In this format, contracts (or waqf declarations) could be converted to computer code, stored and replicated on the system and supervised by the network of computers that run the blockchain. This would also result in ledger feedback such as transferring money out of the waqf and funding the khayrat or a’akarat

3) Estate

The estate (also known as a’aqarat, al-mawqūf or al-muḥabbas) used to found a waqf must be objects of a valid contract (which we have already covered earlier). Obviously, the object should not be illegal in Islam (e.g. alcohol, gambling or pork). Finally, these objects should not already be in the public domain. As my dear mentor, Aamir Rehman is fond of saying: “I cannot sell you the Brooklyn Bridge.” Thus, public property cannot be used to establish a waqf. The founder cannot also have pledged the property previously to someone else i.e. you cannot have your waqf and eat it to.

Traditionally, the estate or a’aqarat dedicated to waqf is generally immovable, such as real estate, however, many movable (and perhaps even intangible) goods can also form waqf, according to most Islamic jurists. Some jurists have argued that even gold and silver (or flimsy fiat currencies) can be also be designated as waqf. Would be interesting to see those some jurists debate the jurisprudence of cryptocurrencies.

4) Beneficiaries

The beneficiaries of the waqf can either be persons or intersubjective public entities. Traditionally, the founder can specify which persons are eligible for the benefit (such as the founder’s family, the entire community, or only the poor). Public utilities such as mosques, schools, bridges, graveyards, drinking fountains and water wells are the usual beneficiaries of a waqf in many a Muslim country.

Modern legislation sometimes classifies different waqfs as either “charitable causes”, in which the beneficiaries are the public or the poor) and “family” waqf, in which the founder makes the beneficiaries his relatives (the extension of the family is also up to interpretation). However, these are not MECE categories as there can also be multiple beneficiaries. For example, the founder may stipulate that half the proceeds of his or her waqf go to his family, while the other half goes to different public entities.

Valid beneficiaries must satisfy the following conditions:

- They must be identifiable. At least some of the beneficiaries must also exist at the time of the founding of the waqf. The Mālikīs, however, hold that a waqf may exist for some time without beneficiaries, whence the proceeds accumulate are given to beneficiaries once they come into existence. An example of a non-existent beneficiary is an unborn child

- The beneficiaries must not be at war with the Muslims. Scholars stress that non-Muslim citizens of the Islamic state (dhimmi) can definitely be beneficiaries

- The beneficiaries may not use the waqf for a purpose in contradiction of Islamic principles

There is a dispute amongst scholars over whether the founder himself can reserve exclusive rights to use waqf. Most scholars agree that once the waqf is founded, it can’t be taken back. On this, the blockchain would hold no objection, however, a more abject concern is token incentivize protocol adoption amongst potential crypto-waqf beneficiaries and how it affects value distribution via what is called the token feedback loop.

You see, when a token appreciates in value, it draws the attention of early speculators, developers and entrepreneurs. They become stakeholders in the protocol itself and are financially invested in its success. This creates an unfavorable temptation amongst some of these early adopters, perhaps financed in part by the profits of getting in at the start, to build products and services around the protocol, recognizing that its success would further increase the value of their tokens. Yes, some of these products become successful and bring in new users to the network and perhaps new VCs and other kinds of investors. This would further increase the value of the tokens and draw more attention from more entrepreneurs, which in turn would lead to more applications, and so on.

There are two things worth pointing out about the token feedback loop. First is how much of the initial growth is driven by speculation (which is both anti-Islamic Finance and anti-Value Investing). Most tokens are programmed to be scarce, as interest in the protocol grows so does the price per token and thus the market cap of the network. Sometimes interest grows a lot faster than the supply of tokens and it leads to bubble-style appreciation of Hormozdian proportions.

With the exception of deliberately fraudulent schemes, this could be considered a good thing (especially if you are in Silicon Valley) as speculation is often the engine of technological adoption. Indeed, both aspects of irrational speculation — the boom and the bust — can be very beneficial to technological innovation. The boom should attract financial capital through early profits, some of which are even reinvested in innovation (how many of Ethereum’s investors were ready to re-invest their Bitcoin profits, or DAO investors their Ethereum profits?), and the bust can actually support the long-term adoption of the new technology as prices will eventually depress and out-of-the-money stakeholders look to be made whole by promoting and creating value around it (just look at how many of today’s Bitcoin companies were started by early adopters after the crash of 2013).

The second aspect worth pointing out is what happens towards the end of the loop. When applications start to emerge and show early signs of success (whether measured by increased usage or by the attention (or capital) paid by financial investors), two things happen in the market for a protocol’s token: new users are drawn to the protocol, increasing demand for tokens (since you need them to access the service or utility), and existing investors hold onto their tokens anticipating future price increases, further constraining supply. The combination forces up the price (assuming sufficient scarcity in new token creation), the newly-increased market cap of the protocol attracts new entrepreneurs and new investors, and the loop repeats itself.

This is the part I personally have an issue with and I generally consider anti-Shariah as arbitrary inflation of a service or dilution of a product beyond its ‘fair-price’ is not in line with Islamic principles.

5) Administration

Usually, a waqf has a range of beneficiaries. Thus, the founder makes arrangements beforehand by appointing an administrator (also called a nāẓir or mutawallī or ḳayyim) and lays down the rules for appointing successive administrators. The founder may himself choose to administer the waqf during his lifetime. In some cases, however, the number of beneficiaries is quite limited. Thus, there is no need for an administrator, and the beneficiaries themselves can take care of the waqf.

This is where the blockchain could really galvanize the waqf. Having the community administer the waqf through the blockchain’s administrative interface, which supports the basic management of the network (deploy, undeploy, ping, update) thus working with both the members (beneficiaries) and assets (a’aqarat).

Similar to the founder, the administrator, like other persons of responsibility under Islamic law, must have the capacity to act and contract. In addition, trustworthiness and administration skills are required. Some scholars require that the administrator of this Islamic religious institution be a Muslim, though the Hanafis drop this requirement. This opens us up to the same privacy concerns when it comes to uncovering the details of the founder. There is no doubt that some level of transparency and real-world accountability is required when permitting the founder or the administrators into the crypto-waqf web.

Also, remember that earlier part about thin and fat protocols? The beauty of the blockchain is that it would keep all the value in the protocols and not in the application (administration) of the waqf, thereby creating more value for the beneficiaries and avoid current day horror stories of various charities and waqf administrators charging 15 to 25% of the estate and its income as administration fees. So much for the hallowed 2+20!

6) Termination

Traditionally, a waqf is intended to be perpetual and last forever. Therefore, one could really only expect a waqf to be managed in perpetuity if it was beholden to the blockchain. Nevertheless, Islamic law envisages conditions under which the waqf may be terminated:

- If the goods of the waqf are destroyed or damaged. Scholars interpret this as the case where goods are no longer used in the manner intended by the founder. The remains of the goods are to revert to the founder or his/her heirs. Other scholars, however, hold that all possibilities must be examined to see if the goods of the waqf can be used at all, exhausting all methods of exploitation before the termination. Thus, land, according to such jurists, can never become extinguished and perhaps the same could be said of cryptocurrencies, even though we all have that one friend who somehow corrupted his thumb drive full of crypto.

- Obviously, a waḳf can be declared null and void by the ḳāḍī, or religious judge, if its formation includes committing acts otherwise illegal in Islam, or it does not satisfy the conditions of validity, or if it is against the notion of philanthropy. One could imagine that a crypto-waqf would be policed by a digital Shariah board rather than a single authoritarian person or legal entity. Indeed, the disruption of the judicial branches of government (and perhaps even the legislative branches) is another strong promise of the blockchain.

- According to the Mālikī school of thought, the termination of the waqf may be specified in its founding declaration. As the waqf would expire whenever its termination conditions are fulfilled (e.g. the last beneficiary). The waqf property then returns to the founder, his/her heirs, or whoever is to receive it according to the founder’s original will.

A Final Word on Fidelity

Rest assured, whether it’s a waqf in its most traditional sense or a new-era crypto-waqf contrivance — the single most important currency is the ability to create a single version of the…truth. From an ethical standpoint, it is this principle of fidelity that broadly requires that we act in ways in which we are loyal and accountable to one another a single human society. This includes keeping our promises, doing what is expected of us, performing our duties and being ultimately…trustworthy.